In many disciplines the significance of findings is judged by P values. They are used to test (and dismiss) a ‘null hypothesis’, which generally posits that the effect being tested for doesn’t exist. The smaller the P value that is found for a set of results, the less likely it is that the results are purely due to chance. Results are deemed ‘statistically significant’ when this value is below 0.05.

But many scientists worry that the 0.05 threshold has caused too many false positives to appear in the literature, a problem exacerbated by a practice called P hacking, in which researchers gather data without first creating a hypothesis to test, and then look for patterns in the results that can be reported as statistically significant.

So, in a provocative manuscript posted on the PsyArXiv preprint server on 22 July, researchers argue that P-value thresholds should be lowered to 0.005 for the social and biomedical sciences. The final paper is set to be published in Nature Human Behaviour.

Why 0.005?

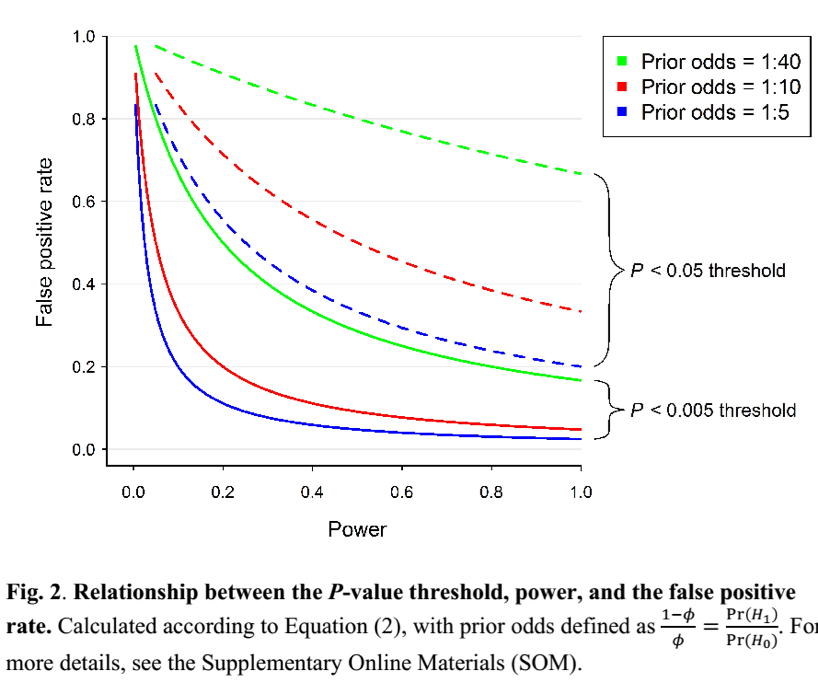

The choice of any particular threshold is arbitrary and involves a trade-off between Type I and II errors. We propose 0.005 for two reasons. First, a two-sided P value of 0.005 corresponds to Bayes factors between approximately 14 and 26 in favor of H1. This range represents “substantial” to “strong” evidence according to conventional Bayes factor classifications.

Second, in many fields the P < 0.005 standard would reduce the false positive rate to levels we judge to be reasonable.

“Researchers just don’t realize how weak the evidence is when the P value is 0.05,” says Daniel Benjamin, one of the paper’s co-lead authors and an economist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. He thinks that claims with P values between 0.05 and 0.005 should be treated merely as “suggestive evidence” instead of established knowledge.

Super-sized samples

One problem with reducing P-value thresholds is that it may increase the odds of a false negative — stating that effects do not exist when in fact they do — says Casper Albers, a researcher in psychometrics and statistics at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. To counter that problem, Benjamin and his colleagues suggest that researchers increase sample sizes by 70%; they say that this would avoid increasing rates of false negatives, while still dramatically reducing rates of false positives. But Albers thinks that in practice, only well-funded scientists would have the means to do this.

Shlomo Argamon, a computer scientist at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, says there is no simple answer to the problem, because “no matter what confidence level you choose, if there are enough different ways to design your experiment, it becomes highly likely that at least one of them will give a statistically significant result just by chance”. More-radical changes such as new methodological standards and research incentives are needed, he says.

Lowering P-value thresholds may also exacerbate the “file-drawer problem”, in which studies with negative results are left unpublished, says Tom Johnstone, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Reading, UK. But Benjamin says all research should be published, regardless of P value.

Yet other scientists have abandoned P values in favour of more-sophisticated statistical tools, such as Bayesian tests, which require researchers to define and test two alternative hypotheses. But not all researchers will have the technical expertise to carry out Bayesian tests, says Valen Johnson, who thinks that P values can still be useful for gauging whether a hypothesis is supported by evidence. “P value by itself is not necessarily evil.”

信息来源:

- http://www.nature.com/news/big-names-in-statistics-want-to-shake-up-much-maligned-p-value-1.22375

- https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/mky9j